Factories Tables Revolution Economy

From Revolutionary Trade to the Socialist Market Economy

Ho Rui An and Zian Chen

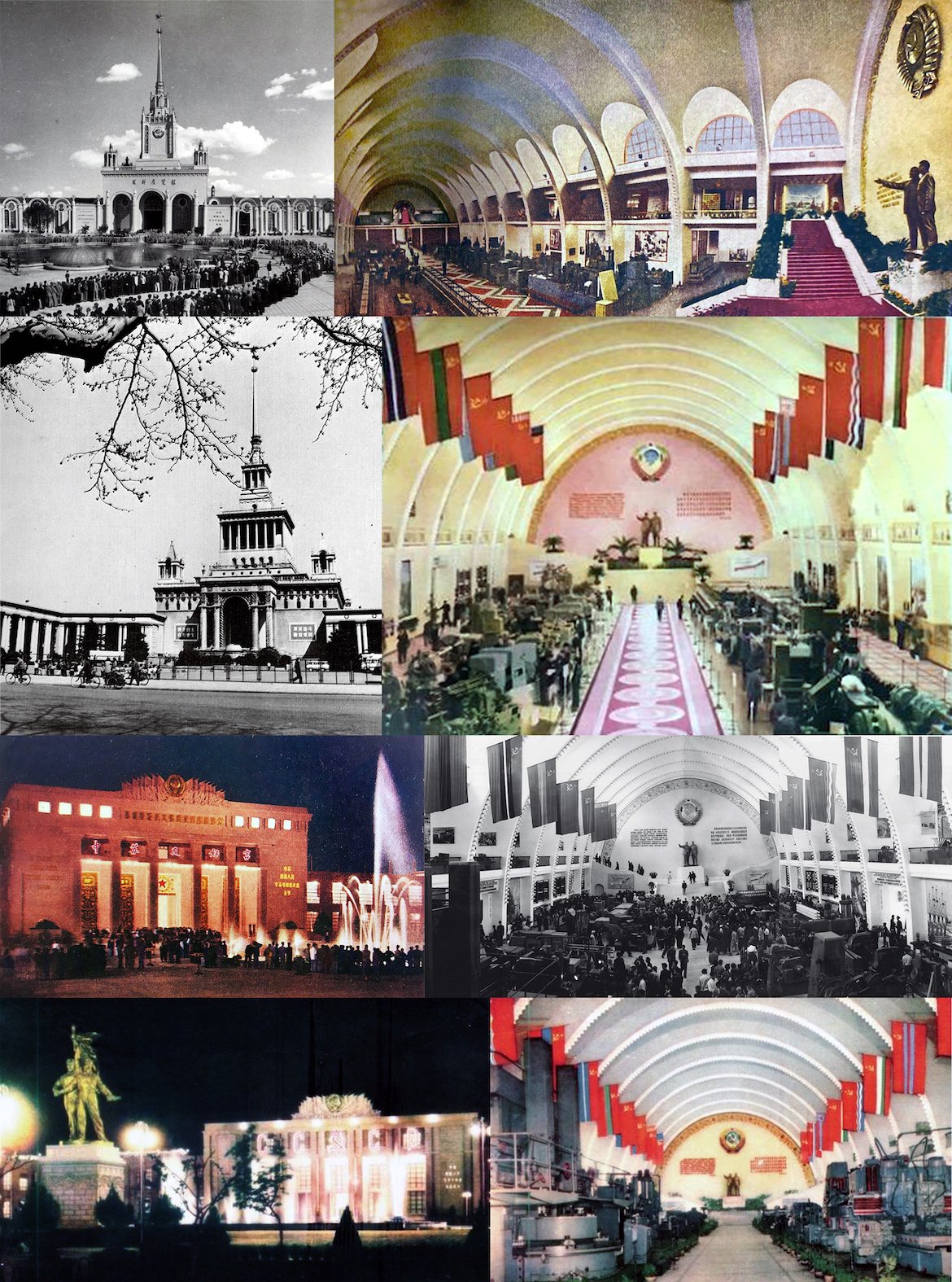

1954–57

Between 1954 and 1956, four exhibition halls with Stalinist architectural features were built in Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan and Guangzhou. The images show all four venues hosting the exhibition “The Soviet Economic and Cultural Achievements” during those years. Source: Beijing: Chaohua Fine Arts Publishing, 1955; Shanghai: People’s Fine Arts Publishing, 1955; Wuhan: Hubei People’s Publishing, 1956; Guangzhou: South China People’s Publishing, 1955.

Regarding our strategy for improving relations with Western nations, in politics there is “peace”, in economics there is “trade”. – Zhou Enlai, August 12, 1954.¹

For most people today, the words “foreign trade” would immediately conjure images of the boundlessness of global capitalism. Yet, for someone living in southern China during the mid-twentieth century, foreign trade was something to be experienced within an enclosed space. One such space was the Sino-Soviet Friendship Hall in Guangzhou where the first China Import and Export Fair, better known as the Canton Fair, was held in the spring of 1957. Despite the imposing Stalinist architectural features of the building—likewise observed in the three other exhibition halls built in Beijing, Shanghai and Wuhan between 1954 and 1956—the biannual fair was envisioned as an “open window” for socialist China to carry out commercial and diplomatic exchanges with the wider world, including with countries that followed a capitalist system.²

This socialist marketplace has a specific geopolitical origin: despite the vast Soviet technological transfers and investments into the country’s heavy industry sectors, the Communist Party of China struggled with rising debts amidst a prolonged embargo imposed by the US on Chinese trade. The Canton Fair was thus conceived with the expressed aim of accumulating foreign currency reserves to combat the “economic Cold War”.³

Furthermore, their experience with several trade missions in the years leading to the fair’s opening also showed the leaders in Beijing how expanding trade with capitalist nations in Europe, especially Britain, sowed discord between Washington and its allies. On the eve of the fair’s opening, exemptions being granted to steel manufacturers in Japan and at least ten European countries were already allowing them to export in limited quantities to China in a threat to the US-led embargo.⁴

With more firms demanding greater access to the Chinese market, it did not take long for the Canton Fair to quickly grow to account for up to two thirds to the country’s exports, with the increase in trade coming not just from US allies but also from overseas Chinese business networks in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. As Sino-Soviet relations deteriorated towards the 1960s, British Hong Kong became the socialist nation’s top trading partner.⁵

1958

Stills from Huang Baomei (1958), directed by Xie Jin. Source: Shanghai Tianma Film Studio.

In 1958, fears that the ongoing de-Stalinisation campaign in the Soviet Union would threaten Mao’s legitimacy within China prompted the launch of the Great Leap Forward, a far-reaching and ultimately devastating experiment that sought to delink the country’s economy from the Soviet model. Anticipating the withdrawal of Soviet aid and technological transfers, the Party turned to mass mobilisation as a solution for spurring productivity and innovation within the mostly agrarian population. In particular, the self-organisation of workers was promoted as a method for meeting the increased production targets under austerity conditions.

Within the film industry, such strategies resulted in many productions taking form as docudramas, the genre most favoured by premier Zhou Enlai for its faster turnover rates, lower budgets and collective scripting process.⁶ Among the docudramas produced during this period was Huang Baomei (1958), based on the story of its titular protagonist and real-life model worker. The climactic scene in the film shows enterprising female factory workers, all played by actual workers, furiously debating technicians and party cadres on the relationship between labour and technology. At the heart of the debate is the question: is it man who masters the machine or the machine that masters man?

Such an extended sequence featuring workers engaging in ideological debate was a recurring motif in Chinese socialist cinema. In contrast to their counterparts in early Soviet cinema who were often depicted working frenetically at their machines in a fetishistic fusion of labour and technology, here the workers are more likely seen having meetings where they can never seem to stop talking about their machines.

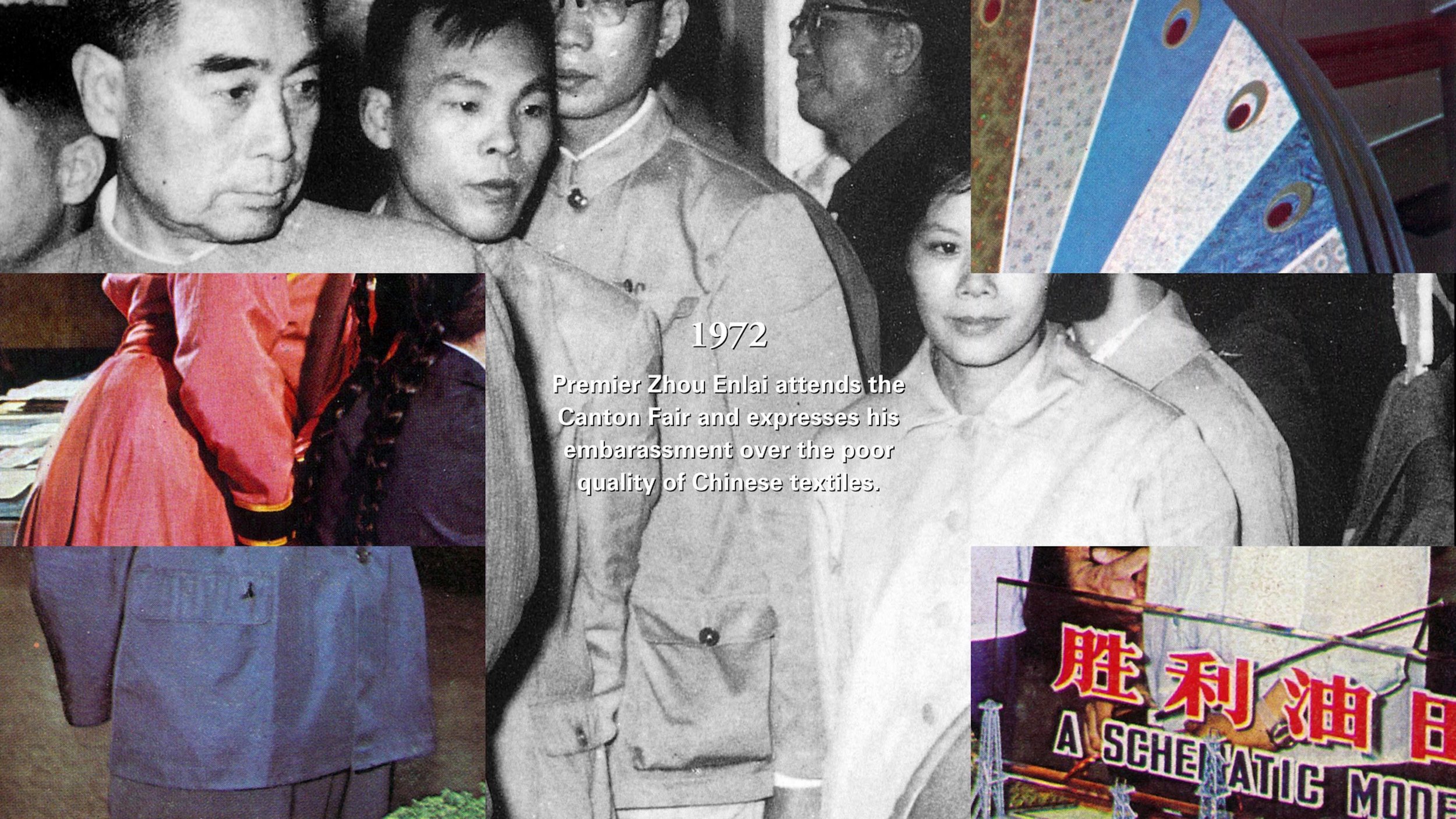

1967–74

Zhou Enlai meeting the Red Guards in Guangzhou, 1967.

Source: United Daily News Archive.

During the heyday of the Cultural Revolution, the purging of purported class enemies by the youth-led shock troops known as the Red Guards penetrated all levels of public life. In spring 1967, the ideological crusade would find its way to the Canton Fair—in clear defiance of a directive issued by Mao for the trade fair to proceed undisturbed.

It would take a last-minute intervention by Zhou Enlai on April 14 to save the fair from being taken over by the young radicals. In his speech addressed to the leaders of the Red Guards who had gathered at the fair, the premier defended the fair through the rhetoric of class struggle: “We must use the trade fair to showcase the new political and economic outlook of our country, so as to expand the political influence of our Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution across the world, and debunk the rumours and slanders made by class enemies of the Revolution both at home and abroad… We must raise the great red flag of Mao Zedong Thought and work together to make the trade fair a success.”⁷

Such conflicts between figures of authority and those self-identifying as “the masses” frequently occurred as the pursuit for higher productivity continually breached hardening ideological lines. Sometimes, workers frustrated by the indifference of their managers would even turn to writing big-character posters to express their grievances, as a group of workers at a computer factory did in Shanghai in 1974: “The management follows the line of experts instead of the mass line; to build a computer one must know not only how to connect the lines but also where to draw the line!” The response from the managers turned out to be affirmative: “Proletarian politics must take command over the building of machines. To make a machine is to make a people. The mass line governs all lines.”⁸

1972–78

Still from Lining (2021), directed by Ho Rui An. Source: the author.

Following Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China, American businessmen were invited to the Canton Fair for the first time. That year, Zhou Enlai was likely influenced by the American presence at the fair when he complained that the quality of the Chinese textile goods being sold was so poor that they presented a very bad image of the country. ⁹ So, when a proposal came from the Ministry of Light Industries in the same year to import technology to produce synthetic fibres, the idea easily won the approval of the premier, allowing the first imports to arrive from France and Japan soon after. ¹⁰

In the following year, this initial push for imports accelerated into a “great leap forward” into capitalist markets with the approval of the “Four-Three” programme, which took its name from the colossal US$4.3 billion worth of technology and equipment that would be bought from the capitalist world within the next three to five years. In its rationalisation of this ambitious plan, the leadership cited the growing economic malaise within developed capitalist nations that compelled firms to seek new investments abroad.¹¹ It was also not lost upon them that, within the region, economies such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore—the so-called Asian dragons or tigers—have long already been reaping the benefits of global economic integration.¹²

In fact, these “change of winds” that would soon arrive in China were already being observed by the foreign minister of Singapore, S. Rajaratnam, at the summit of the Non-Aligned Movement that year when he called for non-aligned countries to disentangle themselves from ideological struggles and focus instead on technological autonomy and economic cooperation.¹³ He also believed that the best way to do so was by embracing the global market, as demonstrated by Singapore’s own economic successes. This was coming just one year after the emissary of the former British colony had proclaimed the city-state to be a “global city” in a now-historic address that vividly describes a global “chain of cities” connected “through the tentacles of technology”.¹⁴

It was therefore appropriate that Rajaratnam would in 1975 become one of the first diplomats from the capitalist world to visit China after Nixon. The moment anticipated later high-profile exchanges between the leaders of the two countries that culminated in senior vice-premier Deng Xiaoping’s first and only state visit to Singapore in November 1978, one month before the reform and opening up agenda was announced in China.

1979-80

Soldiers from the border defence force laying cables along the Second Line in Shenzhen, 1984. Source: Zhong Guohua.

In January 1979, China Merchants Group was given approval by the State Council to assume full control over the development of the 2.14-kilometre-square Shekou Industrial Zone located within the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ). There was perhaps no other entity more equipped to spearhead the experimentation that was to take place within this zone within a zone. As a Hong Kong-based “overseas” company under the auspices of the Ministry of Transportation in Beijing, China Merchants had the experience of operating along the southern frontier where Chinese socialism had long interfaced with global capitalist markets.

But China Merchants was far from the only “red line” institution operating in the British colony during the Maoist era. For one, the organisation of each edition of the Canton Fair would not have been possible without China Resources, another Communist-run company, which facilitated logistical operations and provided access to foreign markets through its base in Hong Kong. Established in 1938 by the Red Army as a military trading outpost, the enterprise had been administered by the Ministry of Foreign Trade from Beijing ever since the founding of Communist China.¹⁵ The crackdown of the 1967 leftist riots in Hong Kong led to the suspension of most “red” activities in the colony but did not entirely dismantle the institutions that allowed the Communist Party to have a foothold in the territory.¹⁶ Following the launch of the economic reforms, many of these institutions were rejuvenated as investment vehicles for bringing in capital and technology through Hong Kong into the Shenzhen SEZ.

It bears mention that the establishment of the SEZ itself as a physically demarcated zone was accomplished by the “reddest” of all institutions. Following the administrative designation of the zone in 1980, an 84.6-kilometre barbed wire fence was erected by soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army to segregate the Shenzhen SEZ from the rest of China. Commonly known as the “Second Line”, the fence was distinguished from the “First Line” between Shenzhen and Hong Kong in that it served not to prohibit movement but to regulate it through the seven checkpoints that allowed only people and goods with permits to move between the zone and the rest of the country where reforms were unravelling at a different pace. One might call this model of “controlled experimentation” the epitome of redness in the Reform era.¹⁷

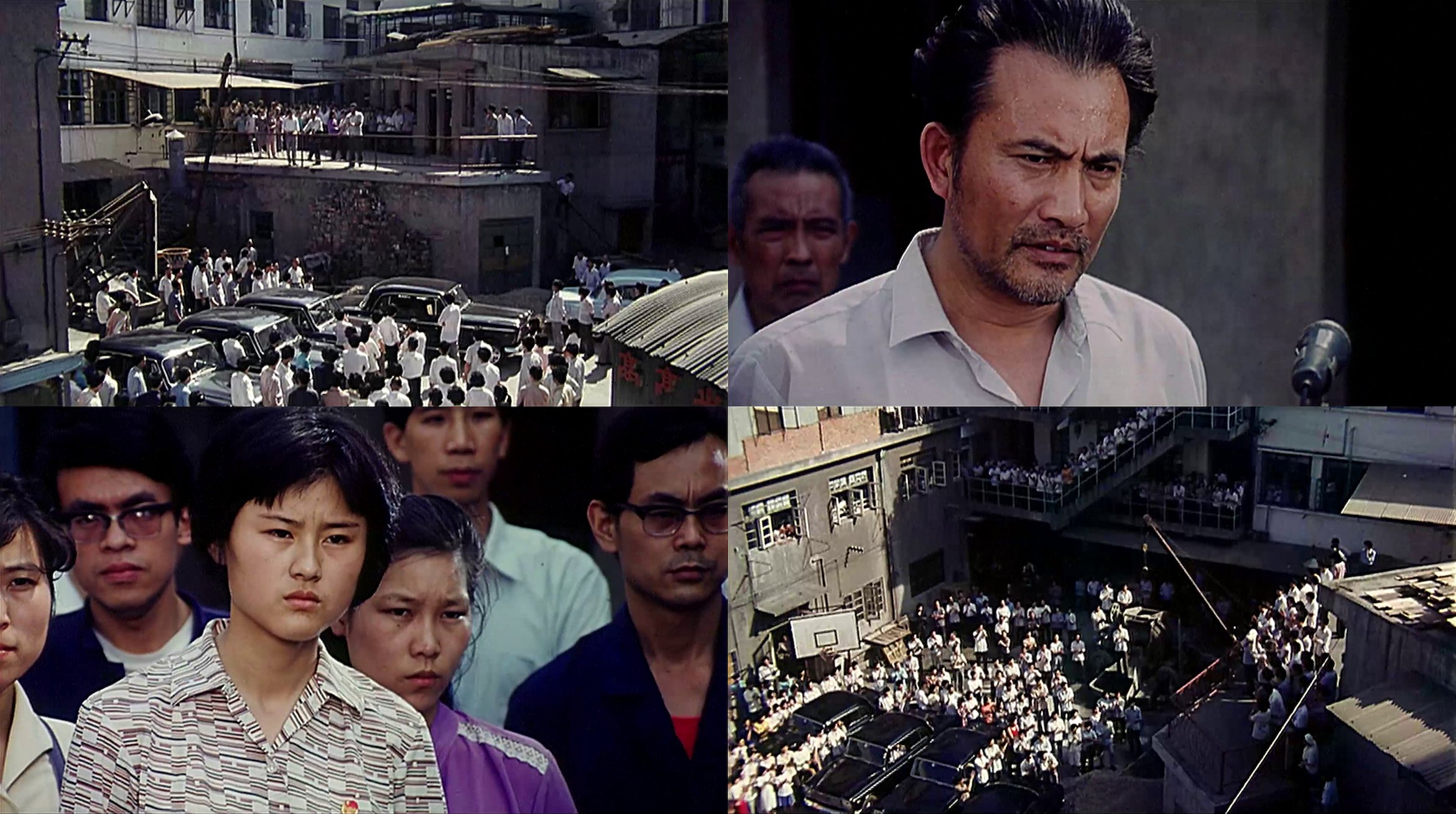

1983

Stills from Blood is Always Hot (1983), directed by Wen Yan. Source: Beijing Film Studio.

Even with the Revolution’s untimely end, former revolutionaries-turned-reformers would continue to mobilise every manner of revolutionary tropes well into the Reform era. This is best observed in a recurring cinematic motif during the first two decades of the economic reforms: the public speech of the determined reformer rallying the support of workers disillusioned by the reform process.

In Blood is Always Hot (1983), which notably opens with a scene set at the Canton Fair, we see the tragic downfall of a state-owned textile mill whose leaders are shown to be incapable of reading and responding to market signals. Despite one eager manager’s intrepid efforts at refitting their printers to produce a more fashionable style, the party secretary in charge of the mill insists upon adhering to old ideological lines.

After facing numerous setbacks, the exasperated manager can only appeal to the workers themselves through a public address in a dramatic final scene where the latter are portrayed as passive listeners, as if they had lost the capacity for speech that had earlier enabled their revolutionary function. Comparing China’s economic system to “a vast machine with rusty gears that can no longer turn”, the manager exhorted the workers to use their “blood as lubricants”, for their blood, he adds, “is always hot”.

With that final proclamation, the spectre of mass mobilisation once again rears its head. The challenge, as always, to use the words of Elizabeth J. Perry, is “how to put the genie of mass protest back into the bottle of state socialism”.¹⁸

1992

Meetings between Chinese and Singaporean officials during a study mission to Singapore in 1995. Source: National Archives of Singapore.

In 1992, three years after the traumatic events of Tiananmen Square, Deng Xiaoping sought to put the reform agenda back on track by going on a tour of the southern provinces where the SEZs are concentrated. The ageing stateman had realised by then that one could not simply opened up the market without accounting for its social consequences. With the resumption of the reforms, society had to be disciplined. This was made clear during a speech where he instructed officials to learn from Singapore with respect to how they managed society. ¹⁹ A few months later, Xu Weicheng, the deputy head of the propaganda department, led a delegation of Chinese officials on a twelve-day study mission to the city-state, the first of many such missions to come.

In the same year, Deng’s successor Jiang Zemin devised the term “socialist market economy” to describe the new direction of the reforms. For the first time in its history, the Communist Party was speaking of the country’s economy not as the revolution’s material base, but as “the economy”. For the first time, the economic struggle was disarticulated from class struggle. However, this did not, at least by the leadership’s own reckoning, mark a shift towards capitalism, for markets, they insisted, are not exclusive to capitalism, as proven by the existence of the Canton Fair. Rather, what changed with the socialist market economy is that now the market would make visible for the socialist party-state what it was previously unable to see: the economy.²⁰

Exactly how the market enables the party-state to better see the economy is revealed by the photographs of the numerous study missions undertaken by Chinese officials to Singapore since 1992. As seen in the images of the many meetings held between officials from both countries, it was only by first sitting at large tables in rooms from which the masses had been entirely evacuated that these former revolutionaries were able to free themselves from the ideology in their minds and look objectively at the information presented before them. Through studying the information provided by the market, they would reinvent themselves as technocrats capable of “seeking truth from facts”, as opposed to being swayed by the fervour of the masses.²¹ Yet, these officials who had been through the throes of the Revolution also knew all too well that the masses had not disappeared, merely retreated. Indeed, the very emptiness of the table in these photographs suggest that a space has been cleared for their return.

¹ Zhou Enlai, "Report on Diplomatic Issues" (guanyu waijiao wenti de baogao), August 12, 1954, Fujian Provincial Archives.

² China Foreign Trade Centre, Personal Experiences of the Canton Fair (qinli guangjiaohui) (Guangzhou: Southern Daily, 2006), 224–26.

³ Shu Guang Zhang, Economic Cold War: America's Embargo Against China and the Sino-Soviet Alliance, 1949–1963 (Redwood City, California: Stanford University Press. 2002).

⁴ Jason M. Kelly, Market Maoists: The Communist Origins of China's Capitalist Ascent (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021), 6, 135.

⁵ He Hui, “The Canton Fair and the Opening-Up of China” (guangjiaohui yu zhongguo de duiwai kaifang), in Twenty-First Century (ershiyi shiji), no. 105 (February 2008): 61–70.

⁶ Qi Zhi, The People's Films in the Mao Zedong Era, 1949-1966 (Mao Zedong shidai de renmin dianying 1949-1966 nian) (Taipei: Xiuwei, 2010), 404.

⁷ Zhou Enlai, "Conversation between Zhou Enlai, Foreign Trade Cadres and Representatives of the Masses" (Zhou Enlai yu waihuo bu ganbu he qunzhong daibiao de tanhua) (Guangzhou, April 14,

⁸ Wang Hongzhe, "Machine for a Long Revolution: Computer as the Nexus of Technology and Class Politics in China 1955–1984” (manchang de dianzi gemin: jisuanji yu hongse zhongguo de jishu zhengzhi 1955-1984), doctoral dissertation (Hong Kong: The Chinese University, 2014), 153.

⁹Zhou Enlai, "Record of conversation between Premier Zhou and representatives of Canton Fair" (Zhou zongli zai jiejian guangzhou jiaoyihui daibiao de tanhua jilu) (speech, April 9, 1972) in Record of New China's Glorious Twenty-First Century (Huihuang de ershi shiji xin zhongguo de da jilu), eds. Dai Zhou and Wen Kegang (Beijing: Red Flag Publishing House, 1999), 986.

¹⁰ Chen Jinhua, The Eventful Years: Memoirs of Chen Jinhua (Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 2008), 18

¹¹ Kelly, 199.

¹² Ezra F. Vogel, Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011), 125–26.

¹³ Sinnathamby Rajaratnam, “Speech at the 4th Summit Conference of Non-Aligned Countries" (Algiers, September 8, 1973), The S. Rajaratnam Private Papers, ISEAS Library, Singapore.

¹⁴ Sinnathamby Rajaratnam, “Singapore: Global City" (speech, Singapore Press Club, February 6, 1972), National Archives of Singapore.

¹⁵ Cheng Xiang, Hong Kong 1967 Leftist Riots: Understanding Wu Dizhou (xianggang liuqi baodong shimo: jiedu Wu Dizhou) (Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 2018), 89.

¹⁶ Loh, Christine, Underground Front: The Chinese Communist Party in Hong Kong (Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press, 2011), 145.

¹⁷ Sebastian Heilmann, Red Swan: How Unorthodox Policy Making Facilitated China's Rise (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2018).

¹⁸ Elizabeth J. Perry, “Studying Chinese Politics: Farewell to Revolution?" The China Journal, no. 57 (January 2007): 22.

¹⁹ Tong Huaiping and Li Chengguan, Record of Deng Xiaoping's Eight Southern Journeys (Deng Xiaoping baci nanxun jishi) (Beijing: People's Liberation Army Literature and Art Publishing House, 2002), 232–33.

²⁰ For some of the reformers, the key problem of the decentralised economy during the Great Leap Forward were the information distortions created by Mao's directives for local authorities. In turn, “the right kind of decentralization" through the market economy "would generate more information" for making better policy decisions. See Christopher Connery, "Ronald Coase in Beijing," New Left Review 115 (January-February 2019): 36–37.

²¹ Deng Xiaoping, “Emancipate the Mind, Seek Truth from Facts and Unite as One in Looking to the Future" (speech, Beijing, December 13, 1978) in Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, Volume II (19751985) (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1984), 150–63.

Works cited:

Chen Jinhua, The Eventful Years: Memoirs of Chen Jinhua (Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 2008), 18.

Cheng Xiang, Hong Kong 1967 Leftist Riots: Understanding Wu Dizhou (xianggang liuqi baodong shimo: jiedu Wu Dizhou) (Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 2018), 89.

China Foreign Trade Centre, Personal Experiences of the Canton Fair (qinli guangjiaohui) (Guangzhou: Southern Daily, 2006), 224–26.

Deng Xiaoping, “Emancipate the Mind, Seek Truth from Facts and Unite as One in Looking to the Future” (speech, Beijing, December 13, 1978) in Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, Volume II (19751985) (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1984), 150–63.

Elizabeth J. Perry, “Studying Chinese Politics: Farewell to Revolution?” The China Journal, no. 57 (January 2007): 22.

Ezra F. Vogel, Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011), 125–26.

He Hui, “The Canton Fair and the Opening-Up of China” (guangjiaohui yu zhongguo de duiwai kaifang), in Twenty-First Century (ershiyi shiji), no. 105 (February 2008): 61–70.

Jason M. Kelly, Market Maoists: The Communist Origins of China’s Capitalist Ascent (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021), 6, 135, 199.

Loh, Christine, Underground Front: The Chinese Communist Party in Hong Kong (Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press, 2011), 145.

Qi Zhi, The People’s Films in the Mao Zedong Era, 1949-1966 (Mao Zedong shidai de renmin dianying 1949-1966 nian) (Taipei: Xiuwei, 2010), 404.

Sebastian Heilmann, Red Swan: How Unorthodox Policy Making Facilitated China’s Rise (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2018).

Shu Guang Zhang, Economic Cold War: America’s Embargo Against China and the Sino-Soviet Alliance, 1949–1963 (Redwood City, California: Stanford University Press. 2002).

Sinnathamby Rajaratnam, “Singapore: Global City” (speech, Singapore Press Club, February 6, 1972), National Archives of Singapore.

Sinnathamby Rajaratnam, “Speech at the 4th Summit Conference of Non-Aligned Countries” (Algiers, September 8, 1973), The S. Rajaratnam Private Papers, ISEAS Library, Singapore.

Tong Huaiping and Li Chengguan, Record of Deng Xiaoping’s Eight Southern Journeys (Deng Xiaoping baci nanxun jishi) (Beijing: People’s Liberation Army Literature and Art Publishing House, 2002), 232–33.

Wang Hongzhe, “Machine for a Long Revolution: Computer as the Nexus of Technology and Class Politics in China 1955–1984” (manchang de dianzi gemin: jisuanji yu hongse zhongguo de jishu zhengzhi 1955-1984), doctoral dissertation (Hong Kong: The Chinese University, 2014), 153.

Zhou Enlai, “Conversation between Zhou Enlai, Foreign Trade Cadres and Representatives of the Masses” (Zhou Enlai yu waihuo bu ganbu he qunzhong daibiao de tanhua) (Guangzhou, April 14, 1967), Banned Historical Archives, https://banned-historical-archives.github.io/articles/d30b0ab947/).

Zhou Enlai, “Record of conversation between Premier Zhou and representatives of Canton Fair” (Zhou zongli zai jiejian guangzhou jiaoyihui daibiao de tanhua jilu) (speech, April 9, 1972) in Record of New China’s Glorious Twenty-First Century (Huihuang de ershi shiji xin zhongguo de da jilu), eds. Dai Zhou and Wen Kegang (Beijing: Red Flag Publishing House, 1999), 986.

Zhou Enlai, “Report on Diplomatic Issues” (guanyu waijiao wenti de baogao), August 12, 1954, Fujian Provincial Archives.