Memories, Migration and Modernities: China’s Reform as World History

Taomo Zhou in dialogue with Ho Rui An

For the discursive programme, A World of Lines: From Third World Solidarities to Postsocialist Globalism, historian Taomo Zhou presented her ongoing research on the development of Shenzhen, China’s first Special Economic Zone (SEZ) that was established following the launch of its economic reforms. Having grown up in Shenzhen in a migrant family, Taomo has drawn upon her personal memories, along with oral interviews and archival records, in examining this history of China’s transition to the market economy. In this dialogue with artist and PerForm fellow Ho Rui An, she gives us a glimpse into her research process and shares her insights and observations on migration, identity formation and developmentalism within an international history of postsocialism and global neoliberalism.

Rui An (RA): As a historian, your research tends to span different scales of experience, from the perspectives of policymakers to those of grassroots cadres and the masses. For the latter, you often draw upon oral histories. How do you work through the necessarily slippery nature of retrospective oral accounts, and how would you compare that to your approach to materials acquired from state archives, which despite having the permanence of the written word, are also replete with omissions and blind spots, political or otherwise?

Taomo (TM): My first book Migration in the Time of Revolution: China, Indonesia and the Cold War (Cornell University Press, 2019) examines how two of the world’s most populous countries, China and Indonesia, interacted at a time when the concept of citizenship was contested and national identity was fluid. My second book, Made in Shenzhen: A Global History of China’s First Special Economic Zone (under advance contract with Stanford University Press), examines China’s reform and opening through the transformation of one city, now known as the “Silicon Valley of the East” for its concentration of internationally competitive technology firms.

In both projects, I try to integrate the lived experiences of people on the ground with theoretical analysis of broad structural changes in Asia-Pacific geopolitics and economy. In my first book, I want to show my readers how a complex and volatile geostrategic relationship between Beijing and Jakarta reverberated in the classrooms of Chinese-language schools, offices of news agencies and secret headquarters of Chinese political organisations hidden behind the counters of Chinese medicine shops, bakeries and soap factories across Indonesia. In my second book, I want to examine how conflicts, compromises and collaborations between state agents and private entrepreneurs unfolded on everyday bases in the liminal economic space of Shenzhen. If both projects fall into the category of the expanding field of research on “Cold War history”, then my goal is to humanise this broad twentieth-century conflict between different interpretations of Marxism and capitalism.

To transform the embodied, affective and visceral experiences from the bottom up into part of a cross-Asian transnational social history, I weave together public records and personal recollections, while aiming to interpret both kinds of sources with sensitivity to their pitfalls and promises. I have been extremely lucky in terms of access to governmental sources. For my first book, I chanced upon the brief opening of Chinese Foreign Ministry Archives. All the Chinese diplomatic documents I used in the book have been reclassified and are no longer available today. For my ongoing research on Shenzhen, I collected materials from the Bao’an County Archives and the Guangdong Provincial Archives before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Official accounts demonstrate how the post-colonial Asian states intervened in the lives of their citizens in disruptive ways. But the “ordinary people”, who oftentimes appeared nameless and faceless in state sources, also navigated through the Cold War on their own terms and sometimes hijacked or derailed the policy design of state elites.

Oral history is an effective method to balance off the absences, misrepresentations and limitations in state archives. For my first book, I interviewed retired Chinese diplomats, Indonesian Communist exiles as well as residents of the Overseas Chinese Farms, where the ethnic Chinese who migrated to the PRC from abroad were given virgin land on which to rebuild their lives. For the Shenzhen project, I talked to former policymakers, journalists as well migrants of different sorts—diasporic Chinese from Southeast Asia, rural-to-urban migrant workers and state-sponsored technical talents. Understandably, all these memories are socially framed, revised and restricted by the broader environment the narrator is currently situated in. But acknowledging the difficulties of oral history does not mean denying its value.¹ In the highly centralised Party-state of China, state power can still be fragmented and disaggregated, creating loopholes for people on the ground and leaving traces of evidence for me, the researcher.

RA: A key theme in your first book, Migration in the Time of Revolution, is the shifting markers of identity, may it be class, ethnicity or national identification, that were adopted or projected into the Indonesian Chinese during the Cold War. Your current research focuses on the transformation of Shenzhen between the Maoist and Reform eras, especially on the influx of migrants from the rest of China following the launch of the reforms. I'm wondering if you've observed similar transformations in subjectivity among these migrants, especially in terms of the shedding of an identity based on class for one that is more tied to place?

TM: Both my projects on China-Indonesia interactions during the Mao era and on Shenzhen’s urban economic history under Reform focus on the movement, migration and mobility of people and identity changes associated with these processes. Among the Southeast Asian Chinese who resettled on the Overseas Chinese Farms in the People’s Republic as well as state-sponsored, early migrants to Shenzhen, I observe a similar decline of identification as socialist subjects during China’s reform and opening.

In the official mindset of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), diasporic Chinese “returned” to their ancestral homeland even if they themselves had not lived in mainland China previously. They were thus called “returnees” (guiqiao in Chinese).² As historian Glen Peterson points out, the term “return” in the context of the relocation of the overseas Chinese back to China means not merely a reverse movement. It implies a redefinition of oneself from being “Chinese” in terms of cultural identity to being a “socialist subject” in terms of political allegiance, civic responsibilities and obedience to state authority.³

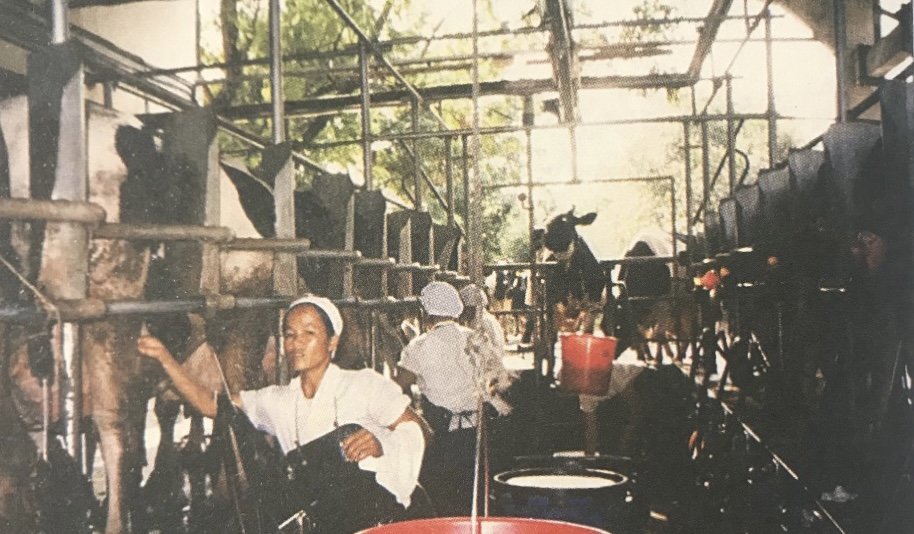

Among the 86 overseas Chinese farms across China, the one that probably enjoyed the highest standard of living was located in Shenzhen.⁴ The state-owned Guangming Overseas Chinese Farm was created by the PRC government to accommodate Malayan, Indonesian and Vietnamese Chinese expelled from Southeast Asia due to local ethnonationalist policies. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Guangming was a state-directed productive space with prominent features of the planned economy, ironically installed as the rest of Shenzhen and China was embarking on market reform. The returnees enjoyed stable salaries, subsidised housing, free medical care and pensions through the first two decades of the reforms. However, as China’s marketisation deepened, the state farm could no longer sustain itself serving simultaneously as an economic enterprise and a social welfare provider. As the farm became restructured into a state-owned enterprise (SOE) and reoriented itself from agriculture to tourism and technological sectors, the returnees and their descendants were expelled from the protective shell of the Chinese state and became marginalised on the drastically transformed farm.⁵

Milk production on the Guangming Farm in the 1990s.

Source: Public Cultural Development Center, Guangming District, Shenzhen City, In Search of Memories of Guangming: The Past Events on the Farm (xunzhao Guangming jiyi: nongchang wangshi) (Shenzhen: Shenzhen News Group Publishing, 2019), 204.

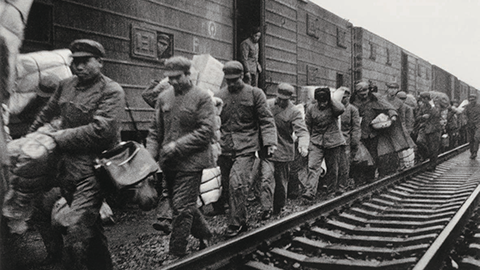

The Guangming returnees’ experiences were in parallel with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Engineering Corps, who erected the wired fences along the “Second Line”—the internal border separating the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone from the Chinese inland. Around the same time when the largest batch of Southeast Asian returnees—ethnic Chinese refugees from Vietnam who were displaced by the Third Indochina War—migrated from one frontier between two warring socialist countries to another frontier between socialist China and capitalist Hong Kong, 20,000 construction PLA soldiers travelled from secret or semi-secret heavy industrial sites to the forefront of China’s market reform. In Shenzhen, the corps’ skills, originally developed to serve the military-industrial complex, were adapted for the construction of civilian infrastructure and public and commercial buildings.⁶

Similar to the state-owned Guangming Overseas Chinese Farm, the PLA Engineering Corps were dissolved and restructured into SOEs. Since their demobilisation in 1983, the ex-servicemen have benefited unevenly from the SOE reforms, arriving at drastically different levels of material wellbeing. Among them are successful entrepreneurs such as Ren Zhengfei, the CEO of Huawei, the world’s largest telecommunications equipment manufacturer. Veterans with low levels of educational attainment have experienced downward social mobility.⁷ In November 2005, more than 3,000 demobilised construction soldiers, angry with the meagre buyouts offered by the privatizing SOEs, organised a sit-in outside the Shenzhen Municipal Government building and were ultimately dispersed by riot police⁸.

PLA Engineering Corps arriving in Shenzhen.

Source: Zhou Shunbin.

The Southeast Asian diaspora and the Second Line construction soldiers complicate our understanding about migration and urban development in Shenzhen. While Shenzhen is commonly understood as a blank slate without socialist past populated by young labourers released from the villages following rural de-collectivisation, these two groups of migrants show the diversity of its migrant population and the continuity between Mao’s revolution and Deng’s reforms. Both groups were simultaneously agents and targets of China’s market reform. Through their labour in high-protein food production, most prominently milk, the Southeast Asian returnees on the Guangming Farm accumulated foreign currency for Shenzhen’s later economic growth through exporting to Hong Kong. As a highly disciplined labour force of Mao’s command economy, the PLA Engineering Corps—the “reddest” of all institutions as you and Zian Chen put it in your essay—constructed the transportation and telecommunication networks that facilitated the circulation of commodities and capital between Shenzhen and the world. Both groups identify themselves as the pathbreakers of Shenzhen and distinguish themselves from the economic migrants who arrived after the 1990s. Having arrived in Shenzhen at a time when the city’s status very low in the spatial hierarchy of China, the construction soldiers and the diasporic returnees believe they deserved preferential treatment from the state as firstcomers.⁹ Yet today, many among the Guangming returnees and the former construction soldiers feel left out of Shenzhen’s metropolitan development.

RA: You've shared that you yourself grew up in a migrant family in Shenzhen. How much of that experience has informed your current research and how has revisiting the history of Shenzhen from the perspective of a historian changed the way you see some of your childhood experiences?

TM: My second book is tentatively entitled Made in Shenzhen. Having grown up in a migrant family in the SEZ, I am “made in Shenzhen” myself. In 1994, I took a week-long train ride with my mother from Harbin to Shenzhen. There we joined my father, an electric engineer whom the state has assigned to help in solving the energy crisis that was plaguing Shenzhen due to a shortage of infrastructure and technical professionals. Although my father was inclined to return to Harbin at the completion of his assignment, my mother insisted that we stay. An economic historian by training, my mother was confident that Shenzhen promised a better future for our family. Almost three decades later, my father still believes that what really motivated my mother to settle in the subtropics was her desire to wear skirts all year long, something impossible in our much colder home city close to Russia.

Like millions of other migrants in Shenzhen, our family developed different identities from those we experienced in the socialist heartland of northeast China. After twenty years of service at a state-owned, coal-fired power station, my father would conclude his lifelong career in the energy sector at a private solar power plant. Meanwhile, my mother taught “Western” micro- and macroeconomics instead of Marxist political economy at Shenzhen University, establishing herself as a prominent scholar specializing in SEZ studies. I spent my teenage years celebrating birthdays at McDonald’s, immersed in Cantonese and English-language TV shows transmitted from Hong Kong. I became a “second-generation Shenzhener” (Shen er dai in Chinese), one of the children of pioneer professionals who arrived in Shenzhen during the early reform era. Mostly transplants from elsewhere in China, my generation of residents nevertheless represents the quintessential Shenzhener today, as our migratory experiences embody the openness of the city.

Taomo and parents at the Sea World McDonalds, Shekou, 1994.

Source: the author.

Made in Shenzhen is a sort of homecoming project for me. Through it, I can translate my lived experience of growing up in the SEZ, along with my academic research capacities, into new knowledge about institutional changes in transitional economies. It is a homecoming project also in the sense that my home today, the Jurong area of Singapore, bore strong resemblance to the neighborhood where I grew up, Shekou of Shenzhen. According to an essay on a Singapore governmental website, in the 1970s one would distinctively notice Jurong upon arrival through the sense of smell: “The air is thick with the aroma of toasty biscuits, freshly roasted cocoa from chocolate factories, and the occasional waft of chemicals and exhaust.”¹⁰ Today, smells from nearby oil refineries and biscuit factories trickle through my office window on the Nanyang Technological University campus on the western end of Singapore, evoking my memories in secondary school in Shekou.

Shekou smells like Jurong, and the sensual connection between the two homes of mine is part of the larger story about the proliferation of export-processing zones in Asia and the intra-Asia knowledge transfer. Located on the western coast of Shenzhen, China’s first and most successful special economic zone, this little more than 2-square-kilometre enclave is even more experimental than Shenzhen itself. Established in January 1979, more than one year before the official launch of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, Shekou was the first “test tube” in socialist China that accepted foreign investment. As you mentioned in your essay, in 1978, Deng Xiaoping paid a historic visit to Singapore, which included a tour to the Jurong industrial estate. A year later, the Shekou Industrial Zone was formally established. With the economic architect of Jurong, Goh Keng Swee, serving as an advisor to the Chinese reformist leaders, Shekou was modeled on Jurong’s approach to state-led rapid industrialisation.

RA: This knowledge transfer from Singapore to China makes me think of the diasporic Chinese business networks in the broader region that the reformists drew upon to fuel the industrialisation process. This brings me to the subject of “Chinese capital” that is (again) becoming contested amidst the global economic malaise and renewed geopolitical rivalries. While your earlier work on Indonesia examines the tensions surrounding Chinese capital that first emerged during the colonial period, your current work can be said to speak to the rise of Chinese capital under the so-called socialist market economy. With the ongoing backlash against global neoliberalism and challenges towards the prevailing liberal-democratic system in much of the Western world, the expansion of Chinese capital into global markets has elicited alarm over the potential emergence of a new imperial agenda as much as it has raised the prospects of an alternative world order that can tilt the balance of power towards the so-called global south. How do you think we should approach the subject of “Chinese capital” that can best allow us to understand the complexities of our present historical juncture?

TM: Before we proceed with the discussion, I think it is necessary to clearly define what exactly is “Chinese capital”. The Chinese-Indonesian entrepreneurs I discussed in Migration in the Time of Revolution were diasporic Chinese capitalists largely independent from the PRC state. Although they sought business opportunities in mainland China as any profit-maximising market agents would do and their investment outcomes were inevitably influenced by geopolitical pressures during the Cold War, they were not answerable to the PRC government. Many of them did forge collaborative relationships with Beijing, but most made their own decisions based on economic calculation, ideological inclination or a combination of both. Admittedly, diasporic Chinese capital was, and still is, an important and controversial resource for the PRC state to tap into. But it is dangerous to not to recognise the autonomy of the diasporic entrepreneurs themselves, or to conflate their ethnicity with citizenship and political orientation.

The development of the Reform-era PRC economy is both connected to and different from the history of Chinese diasporic capitalism. As noted by scholars such as Donald M. Nonini and Aihwa Ong, an important agent that sped up production, distribution and consumption on a global scale were diasporic Chinese managerial elites. Their flexible citizenship strategies, transnational mobility and agile, “guerilla style” of management enabled them to form ungrounded, de-territorialised Chinese business empires.¹¹ Impressed by the economic success of the Chinese living overseas during his trips to Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok in the late 1970s, Deng drew two conclusions: first, China needed to replicate the export-oriented economic growth he observed in Southeast Asia by creating “special economic zones” on China’s south coast; second, China needed to invite the Chinese from overseas to “work the same economic miracle in China” through investment.¹² In the early Reform era, Shenzhen, the ancestral hometown of a diasporic population ranging between 110,000 and 350,000, was strategically positioned to channel offshore “Chinese archipelago capitalism”—diasporic business enterprises in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Southeast Asia—onshore to the Mainland.¹³ Although likewise aided by diasporic investments and knowledge transfers, the economic growth within China today is more closely connected to the expansion of PRC state capitalism, in which the Chinese central government maintains control over the accumulation and allocation of financial resources.¹⁴

In face of current anxieties over a new Beijing-dominated imperial order, I think it is important to unpack the complicated adjective of “Chinese” in front of “capital” and to accurately evaluate the role the PRC state plays under specific circumstances. I also think SEZs can serve as a useful intellectual tool for us to understand “Chinese capital,” be it directly state-controlled, privately owned but subjected to the PRC state regulations, or diasporic and relatively independent. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, SEZs were relatively disarticulated pilot sites for the Chinese state to test market-oriented policies before they were introduced into the core of the planned economy. Fast forward to our current moment of assertive Chinese power and prosperity, SEZs are footholds for private and state-owned PRC enterprises participating in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a development strategy that focuses on infrastructure exports to and expansion of trade networks in Asia and into Europe and East Africa. Following the lead of scholars such as Ho-fung Hung and Ching Kwan Lee, I think it would be helpful for us to analyse the so-called “Chinese capital” under particular contexts by paying attention to local initiatives and grassroots improvisions at home and abroad.¹⁵

RA: It seems to me that these anxieties are also a reflection of a certain crisis in the political imagination. Indeed, we appear to be ironically living through a time where there's growing recognition of the injustices of the global capitalist system as well as an inability to imagine a world without capitalism. Even amidst populist calls for revolution across the political spectrum, there is often an ambiguity over what exactly constitutes a revolution in today's terms. In contrast, the twentieth century was marked by numerous historical upheavals that resulted from some kind of revolution. How do you think a re-examination of this history can allow us to overcome the current impasse? Or are we truly living in a time where revolution, for better or worse, has exhausted its historical course?

TM: To answer this question, I would like to return to the story of the Shekou Industrial Zone and its architect Yuan Geng. Yuan Geng is a true revolutionary in terms of both his credentials in the Chinese Communist Party and his vision of modernity. Yuan was a guerrilla fighter during the Second Sino-Japanese War, an intelligence agent based in Southeast Asia in the 1950s and 1960s, a political prisoner during the Cultural Revolution, and a progressive reformer in the Deng era.

In 1978, Yuan, recently released after five-year imprisonment based on unverified espionage charges, was rehabilitated and appointed as the director of the Hong Kong office of China Merchants Group (CMG). Yuan put forward a bold proposal to Beijing, requesting the central government’s authorization for the CMG Hong Kong office to develop an industrial zone in the neighboring Shekou. Yuan’s proposal was quickly approved. Shekou, which was managed not by the local government but by the CMG, became the first “spatio-juridicial enclosure” in China that accepted foreign investment.¹⁶

Yuan is a firm believer in the market mechanism and the importance of integrating China into the global economy. Yuan’s economic vision for Shekou, with its proximity to Hong Kong and advantageous port conditions, was to strategically place the zone in the increasingly globalised process of production and build an externally oriented, sustainable model of growth. He strictly banned entrepôt trade between Shekou and interior China as well as compensation trade from foreign investors as these projects were short-sighted and detrimental to Shekou’s long-term development. Sensitive to the rising world interests in the South China Sea oil and expansion of container shipping, Yuan initiated container manufacturing business and infrastructure building that would make Shekou into a key oil service center in South China and a popular residential area for foreign oil executives. In 1983, Shekou became China’s poster industrial zone with the youngest population (at an average of 24.5 years), the highest level of education (75% college graduates among cadres/ managers), the highest pay for workers (800 HKD per month, higher than Macau), zero unemployment rate and zero felonies.¹⁷

Beyond economic growth, Yuan believed that the essence of reform and opening was to remove political hierarchy and to implement a high degree of socialist democracy. He encouraged the building of an inclusive political space and supported civic associations such as grassroots “media salon” and “pressure groups.” The local newspaper, Shekou News, were given the freedom to openly criticise against the CMG higher management, including Yuan himself, without repercussion. The members of the board of the directors at the CMG were subjected to annual vote of confidence or no confidence. Before the voting, each candidate would give a speech and answer questions from the public. Yuan believed that China will ultimately head towards universal election and Shekou was better equipped than any other place in China to initiate democratic reform.¹⁸ During the annual elections of the management committee of the Shekou Industrial Zone, mobile ballot boxes would travel on site to offices and factory floors, so that Shekou residents did not need to take a leave from work to vote.

In 1986, Yuan was invited to give a lecture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Yuan asked his audience: “Is Shekou Thomas Moore’s Utopia, Tao Yuanming’s Peach Blossom Spring? No, Shekou is a test tube.”¹⁹ Although not a utopia, Yuan did envision a social democracy on a community level, which combined a market economy with a free press, open elections, affordable housing, high-quality public education and green public spaces to provide leisure opportunities to the working class. Perhaps most importantly, he saw the workers of Shekou as participatory citizens rather than dispensable laborers to be capitalised on. These ideas concerning economic and political governance, expressed by a Chinese revolutionary, promise a different future from today’s global neoliberal order.

Yuan Geng giving a lecture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1986. Source: Shekou China Merchants Group Historical Museum.

¹ Taomo Zhou, Migration in the Time of Revolution: China, Indonesia and the Cold War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), 14.

² Zhou, Migration in the Time of Revolution, 192.

³ Glen Peterson, Overseas Chinese in the People’s Republic of China (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2011), 132.

⁴ Han Xiaorong, “The Demise of China’s Overseas Chinese State Farms.” Journal of Chinese Overseas 9: 1 (2013), 40.

⁵ Taomo Zhou, “Dairy and Diaspora: Postponed Reform on the Guangming Overseas Chinese Farm of Shenzhen,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 24: 2(2023), 708-722.

⁶ Taomo Zhou, “From the Third Front to the Second Line: The Construction Soldiers of Shenzhen,” Made in China Journal 5: 3 (2021), 108-113.

⁷ Taomo Zhou, “Maoist Soldiers as the Infrastructure of Reform: The People’s Liberation Army Engineering Corps in Shenzhen,” in Priscilla Roberts ed., Chinese Economic Statecraft from 1978 to 1989: The First Decade of Deng Xiaoping’s Reforms (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), 329-358.

⁸ SCMP Reporter, “Riot Police Move In to Free Mayor; Ex-PLA Men Protest in Shenzhen for Better Compensation,” South China Morning Post, 8 November 2005.

⁹ Zhou, “From the Third Front to the Second Line.”

¹⁰ “Getting Jurong off the Ground: From Swamp to Industrial Powerhouse,” Roots, https://www.roots.gov.sg/en/stories-landing/stories/jurong-industrial-estate/story (Accessed June 10, 2022).

¹¹ Donald M. Nonini and Aihwa Ong, “Chinese Transnationalism as an Alternative Modernity.” In Ungrounded Empires: The Cultural Politics of Modern Chinese Transnationalism, edited by Aihwa Ong and Donald M. Nonini (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 1997), 3–33.

¹² Peterson, Overseas Chinese in the People’s Republic of China, 169–70.

¹³ Jonathan Bach, “Shenzhen: From Exception to Rule.” In Learning from Shenzhen: China’s Post-Mao Experiment from Special Zone to Model City, edited by Mary Ann O’Donnell, Winnie Wong and Jonathan Bach (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2017), 32–33.

¹⁴ Karl Gerth, Unending Capitalism: How Consumerism Negated China’s Communist Revolution (Cambridge University Press, 2020), 4.

¹⁵ Ho-fung Hung, “Rise of China and the Global Overaccumulation Crisis,” Review of International Political Economy 15: 2 (2008), 2019–22; Ho-fung Hung, The China Boom: Why China Will Not Rule the World (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016); Ching Kwan Lee, The Specter of Global China: Politics, Labor and Foreign Investment in Africa (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

¹⁶ Ronan Palan, The Offshore World: Sovereign Markets, Virtual Places and Nomad Millionaires (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003), 1 and 4.

¹⁷ China Merchants Group Office and China Merchants Group History Association, Collected Works of Yuan Geng (Yuan Geng wenji) (internal circulation, 2012), 107.

¹⁸ Ibid., 226.

¹⁹ Ibid., 176.

Works cited:

China Merchants Group Office and China Merchants Group History Association, Collected Works of Yuan Geng (Yuan Geng wenji) (internal circulation, 2012), 107, 176, 226.

Donald M. Nonini and Aihwa Ong, “Chinese Transnationalism as an Alternative Modernity.” In Ungrounded Empires: The Cultural Politics of Modern Chinese Transnationalism, edited by Aihwa Ong and Donald M. Nonini (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 1997), 3–33.

“Getting Jurong off the Ground: From Swamp to Industrial Powerhouse,” Roots, https://www.roots.gov.sg/en/stories-landing/stories/jurong-industrial-estate/story (Accessed June 10, 2022).

Glen Peterson, Overseas Chinese in the People’s Republic of China (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2011), 132.

Han Xiaorong, “The Demise of China’s Overseas Chinese State Farms.” Journal of Chinese Overseas 9: 1 (2013), 40.

Ho-fung Hung, “Rise of China and the Global Overaccumulation Crisis,” Review of International Political Economy 15: 2 (2008), 2019–22; Ho-fung Hung, The China Boom: Why China Will Not Rule the World (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016); Ching Kwan Lee, The Specter of Global China: Politics, Labor and Foreign Investment in Africa (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

Jonathan Bach, “Shenzhen: From Exception to Rule.” In Learning from Shenzhen: China’s Post-Mao Experiment from Special Zone to Model City, edited by Mary Ann O’Donnell, Winnie Wong and Jonathan Bach (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2017), 32–33.

Karl Gerth, Unending Capitalism: How Consumerism Negated China’s Communist Revolution (Cambridge University Press, 2020), 4.

Peterson, Overseas Chinese in the People’s Republic of China, 169–70.

Ronan Palan, The Offshore World: Sovereign Markets, Virtual Places and Nomad Millionaires (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003), 1 and 4.

SCMP Reporter, “Riot Police Move In to Free Mayor; Ex-PLA Men Protest in Shenzhen for Better Compensation,” South China Morning Post, 8 November 2005.

Taomo Zhou, “Dairy and Diaspora: Postponed Reform on the Guangming Overseas Chinese Farm of Shenzhen,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 24: 2(2023), 708-722.

Taomo Zhou, “From the Third Front to the Second Line: The Construction Soldiers of Shenzhen,” Made in China Journal 5: 3 (2021), 108-113.

Taomo Zhou, “Maoist Soldiers as the Infrastructure of Reform: The People’s Liberation Army Engineering Corps in Shenzhen,” in Priscilla Roberts ed., Chinese Economic Statecraft from 1978 to 1989: The First Decade of Deng Xiaoping’s Reforms (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), 329-358.

Taomo Zhou, Migration in the Time of Revolution: China, Indonesia and the Cold War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), 14, 192.